It’s great being married to a feeder

“Anyone who signs up to the stem cell register must have at least a minimal level of goodness,” I was telling our guests on Saturday, not long before they went on their way. And it’s true. You’re offering to help a stranger – if you’re found one day to be a match – with no benefit to yourself. You’re agreeing to create more stem cells than you need to give to someone you don’t know, who will remain anonymous for at least the following two years. It’s a pretty selfless act.

Our guests on Saturday knew a bit about stem cell transplants. Cassie’s husband had signed up to Anthony Nolan‘s stem cell register when he was at university. “To be honest, it was mostly the idea of going in to the student union and increasing any chances of meeting any girls that might be there that got me in the door,” Tim confided to me. And he had been called in for further tests on more than one occasion – although neither in 2005/6, nor a few years later, did he go on to donate.

Before Christmas 2013, he was called in again for further tests. He then didn’t hear anything for a few months, until suddenly, in March 2014, it was “all systems go”. A nurse visited to give him growth hormones; he travelled to London to have the stem cells extracted from his blood.

Tim saved my life.

Gulp.

He was a 10/10 match. Our blood types were the same (BE POSITIVE, or B+ as it’s more commonly known). He was virus-free. And somehow, he created 12 million stem cells to send my way – enough to let us freeze 2 million and be pretty confident the rest would be plenty to maximise the chances of a successful transplant. Whenever I heard the fantastic news that my chimerism tests showed my blood was ‘100% donor’, it was actually ‘100% Tim’. And it still is.

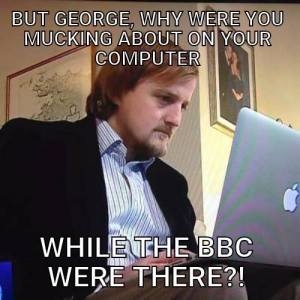

For the two years following my transplant, I was getting on with life powered by 100% Tim blood, but knowing only it was 0% George blood. I’m glad to say he didn’t ask for any of it back when we met for the first time on Saturday.

There have been some particularly special days during my illness, treatment and recovery. Getting into remission; celebrating New Year with Gobby and Angela; going home after weeks, or months in hospital; getting out of Intensive Care; finishing all my treatment the first time around; a joyous Christmas Day with Mariacristina in spite of failing to deal with the relapse; unexpected remission after the MARALL trial; Day Zero: the stem cell transplant; the relief of getting to Day 100; being well enough to get back to work; my first second birthday; my second second birthday. And there have been so many others.

Related by blood?

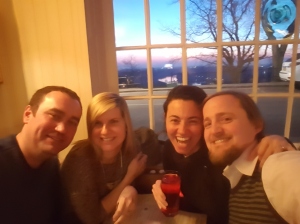

Saturday, though, was something more. Tim, it turns out, has far, far more than the minimal level of goodness I reckon defines anyone who signs up to a stem cell register. He also has a wonderful wife, Cassie, and a gorgeous son, Aldous, born at the beginning of this year. Inviting them to ours for a meal was the very least we could do – and Mariacristina was desperate to cook for the man whose cells had given me all this incredible bonus life. I’m not sure whether 12 million stem cells for a Neapolitan feast is a fair deal – but it’s a start…

Her food blog, Coochinando, was inspired by a desire to give something back after my illness, and is all about showing your love to those you care about through cooking. There was no way Tim was getting away without being fed – and now he even has his own recipe named after him. It also gave Aldous his first taste of tomatoes – though I fear Mariacristina’s gnocchi alla sorrentina sauce may now have set the bar pretty high.

The magic cells

I always knew my donor was just about the same age as me. I knew he was in the UK, and that he was a man. But when you’re recovering from a stem cell transplant, it feels almost presumptuous to start imagining meeting your donor. After all, you need to get to two years post-transplant before you can even suggest exchanging details – and that seems very far off. Even then, the donor might prefer to stay anonymous. Secretly, though, I harboured a small hope that we could one day be friends. It’s a bit demanding, I know: he already gave me 12 million stem cells and saved my life. Don’t be greedy!

It’s easy to write and record songs dedicated to anonymous people (the title of this post comes from my lyrics). And however grateful I felt to my anonymous donor, that anonymity kept the emotional connection at a certain distance. I knew he was out there somewhere, but beyond the (admittedly not insignificant) 0% George cells keeping me alive, he wasn’t any part of my everyday life.

Thwarted!

In April this year, though, when we exchanged details, my donor became real. He became Tim. And on Saturday, Tim became even real-er. We almost managed to meet up a couple of weeks after finding out each other’s name, when my and Mariacristina’s emotions were still running wild, and our heads and hearts were still getting around the enormity of it all. Tim proved, though, that even if his donation had revealed him to be a superhero, he wasn’t invincible; he broke his ankle and everything was postponed.

Various health niggles, football championships and holidays conspired to further delay our first meeting, but meanwhile we got to know each other a bit better via old-school letters (updated to PDF), Facebook stalking and some of our favourite photos. There was Tim, in March 2014, hooked up to the apheresis machine that was extracting his stem cells; another photo showed the bag of cells. I responded with my own photo of the same bag of cells – this time on their way into my body. As an engineer, Tim was fascinated by the process. As a recipient of his stem cells, I was fascinated by Tim.

From Tim…

…to George

I don’t believe in fate. But I’m always ready to celebrate happy coincidences. Tim almost wasn’t my donor. There was a 27-year-old match the doctors/Anthony Nolan were hoping would give his cells, but for some reason it didn’t work out. There’s some poetry in the fact that this allowed Tim to step in – the dates of his previous further checks make it clear he was the one match I knew about back in 2005/6 when I was going through treatment after my first diagnosis and a transplant could have been an option. Our connection goes back to then; he may not have helped save my life that time, but he was there, ready and willing to do so if he’d been needed.

It’s him! It’s me!

In 2014, he was still there. And on Saturday, we met. I burbled various incoherent efforts to express my joy, gratitude and love in Tim’s direction. Mariacristina, the non-native speaker, was far more eloquent. She told him how close she had felt she was to losing me before my transplant, and how special every day since had been – thanks to him. It’s a strange situation; for a donor, the process is short and involves little disruption to life; for a recipient, the transplant is everything – an unexpected bonus chance to live. I feared we would overwhelm Tim and Cassie even more than I’d overwhelmed 7-month-old Aldous with an oversized stuffed elephant.

But they were perfect. They didn’t blink at our excess emotion, but showed they understood, accepted and appreciated what we felt. We all laughed when I threatened to get out my guitar – but I knew I couldn’t get those words out directly to the man for whom I wrote my Donor Song. The delay from April/May had probably been a good thing, we all agreed: the emotional intensity back then would perhaps have been too much. It gave us all a chance to start getting to know each other and build some sort of relationship before we met in person; Tim was no longer simply my only-just-not-anonymous donor – he was, and is, Tim.

A particularly glittery silver lining

He’s still my donor, of course, and always will be. I don’t know where I’d be without him. I don’t know whether I’d be without him. But now he’s real, and he’s family (whether he likes it or not) – as well as a true friend. There have been many silver linings to the cloud of my illness: meeting Tim and his family feels like a particularly glittery one.

Serious illness reminds us life is short. Since my transplant, even before I knew my donor was Tim, I have wanted to make the most of the extra time I have been given. I try to give something back. The big changes in my life that had never seemed so urgent became a priority. I’m still trying to be less scared of doing what I love and saying what I believe. I’m not just grateful to Tim for saving my life. I’m grateful for every extra day his cells have given me. And I’m grateful for everything this extra chance has taught me.

Thank you, Tim.

You, like Tim, could save the life of someone like me. Sign up to a stem cell register at:

Anthony Nolan – if you’re aged 16-30

DKMS (formerly Delete Blood Cancer) – aged 18-55

NHS Bone Marrow Registry – aged 17-40, male, blood donor; or 17-40, female, from Black, Asian, minority ethnicities and mixed ethnicity backgrounds

Well worth the wait!

![20151227_155914 There are lots of fishes [sic] in Pozzuoli](https://betterfools.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/20151227_155914.jpg?w=69&resize=69%2C122&h=122#038;h=122)